BLACK HISTORY MONTH — Goudeau children share cross burning impact; parents’ strong and graceful response

Published 12:40 am Wednesday, February 8, 2023

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

When the Goudeau children were rushed to a bedroom and placed under a bed for safety decades ago, they likely didn’t understand what was going on.

It was Bernard Goudeau, then 4 years old, that noticed the fire outside their Port Arthur home. The significance of the four burning crosses wasn’t lost on the adults.

But it was their mother’s comments that are part of the foundation of faith and family for Bernard and his sister Mary Ann Reid.

“God only makes good people. Sometimes they make bad decisions,” she had said.

Reid was 7 years old at the time of the cross burning. She said, looking back, it wasn’t something her mother chose to talk about. Her comment about God set the tone for their lives.

“Mom didn’t get all hysterical and they didn’t start blaming,” Reid said. “I don’t remember a lot of anger going on about that. And don’t get me wrong, it’s not like it was OK. No, it was this: this was not a good thing. These are the people who lit the large cross for my dad, a medium for my mother and two smaller ones for my brother and I. They were these people who made some very bad choices, but they were still God’s creations.”

While growing up, their home was a gathering place for all.

Bernard Goudeau said it was almost like the United Nations where no matter race, religion or socio-economic status, all were welcome.

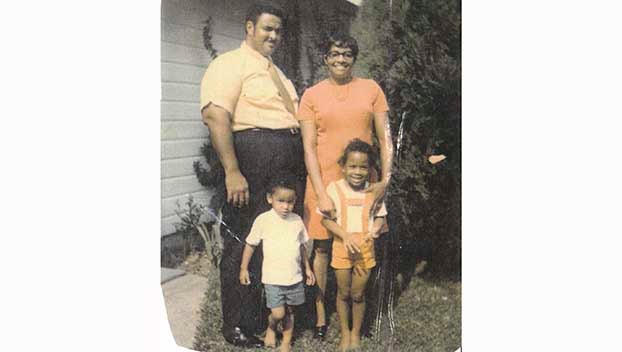

God came first for the family with father Warrington Bernard Goudeau Jr., or W.B. as he was called, wife Doris and their two children.

There was also a strong sense of family, as well as strong African American pride, the siblings said.

W.B. and Doris Goudeau led by example, teaching conservative values while being open minded and accepting individuals who taught their children not to judge.

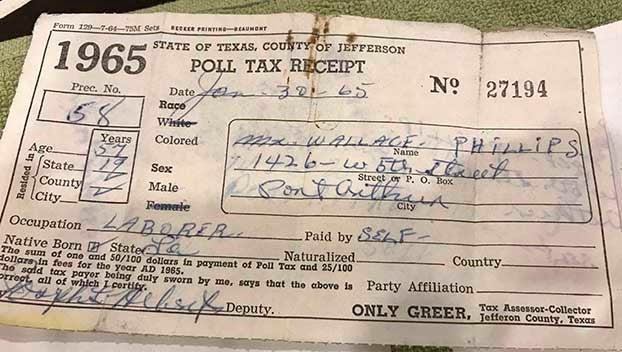

Civil Rights

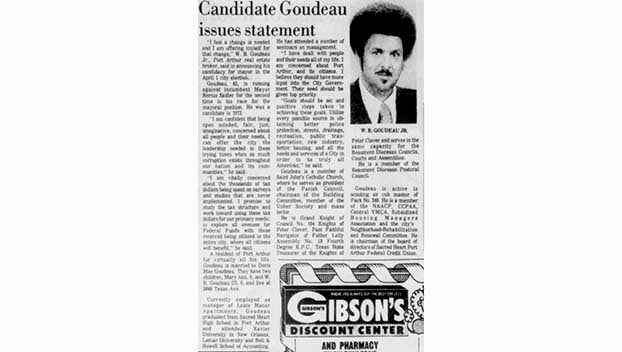

Reid and Goudeau’s father ran for mayor of the city in 1973 — four years after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated and 34 years before Port Arthur elected its first Black mayor. It was during this time the crosses were burned on their lawn.

Their mother was a peaceful person who would internalize everything, analyze it, find a way to deal with it and “just let it kind of roll off her back,” Reid said.

Their father was the opposite. He saw it and would verbalize it. He took up for family and for others around him.

If there was an injustice, W.B. pointed it out by speaking with management over being shorted a piece of chicken or taking up for his wife when she was disrespected.

The couple were cosmically connected, she said. When W.B. would get upset, Doris would place her hand on him and all would be well.

When Doris was in high school, she was part of eight to 10 students who would go with the nuns to sit at Kress’ downtown lunch counter. But she didn’t get served.

One time a girl pretended to faint and the students asked for water. They gave it to her but she could not drink it in the diner.

Later Doris and the others were finally served food but only after a division was built and placed on the counter to separate the two races.

Background

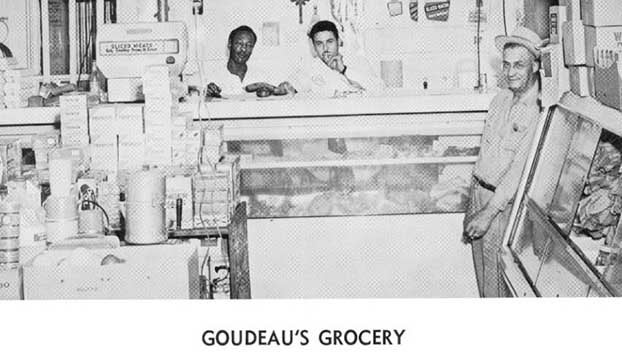

W.B.’s father, Warrington B. Goudeau Sr., owned Goudeau’s Grocery on the West Side of the city, and W.B. worked there for a while. He held many jobs through the years and found ways to help others along the way.

W.B. was awarded a scholarship through the Texas Real Estate Research center and worked toward his Real Estate license, eventually becoming a broker.

Reid said W.B. was able to help people who would otherwise not be able to afford a home. He helped them find houses and was able to help up and coming African Americans who wanted to become real estate agents.

Reid said he was somewhat of an advocate for the African Americans in the city.

“That was how they were able to purchase the land to buy their home,” she said.

W.B. also purchased land near his home on Texas Avenue, later selling what would become the location for Habitat for Humanity homes.

W.B. was later hired to manage the Josephite Housing Complex, Louis Manor Trust Apartments for 26 years.

Then, after Hurricane Harvey hit the area, Reid met with a lady on her mother’s block who was looking for her parents. The lady wanted to thank the Goudeaus for giving the opportunity to become homeowners. If W.B. wouldn’t have sold the land near his home, the property wouldn’t have become available and others wouldn’t have benefitted from it.

Doris held a number of jobs through the years including that of day care and kindergarten teacher — a career she was in for 40 years.

The couple were devout Catholics. Doris prepared children for First Communion and Confirmation. W.B. was advisor to the National Council of Black Bishops and was a member of the Knights of Peter Claver group.

He was on different church committees trying to get the Roman Catholic Church to be more accepting and tolerant of African American desires and the couple was very active in the Beaumont Diocese and studied in a deaconate program.

The legacy

For the Goudeau siblings there was no sitting back and watching. It was all hands on deck, whether it be singing at church, being an altar server or cleaning the church on Saturday mornings.

Goudeau and Reid were taught to be the best they can be at all they do.

“If you’re going to be a garbage man, be the best garbage man you can be. So, you’re a ditch digger. Be the best ditch digger you can be,” Goudeau said, recalling the words of his maternal grandmother. “What mattered was that you gave it your all and pursued excellence at it. Be the best you can be. That stuck with me.

Today, Goudeau and Reid are successful individuals with a strong sense of faith and family. Reid is community advisor with Golden Pass LNG and Goudeau is employed with BASF as assistant general counsel.

While raising their children W.B. and Doris didn’t quote Martin Luther King Jr. but focused instead on the meaning of his words.

“Like I said, everybody, anybody came to the house — white, Black, Hispanic, it didn’t matter. Any and all would come to our home,” Goudeau said. “And everybody was welcomed. So that message that Dr. King was saying about not judging people on the color of their skin but of their character, that wasn’t a message that was pounded on us. It was a message of being of service and being a drum major for change.

“It wasn’t that we were hearing the messages but we were seeing our parents actually do it, being the drum majors for change.”