Texas prosecutors want to keep low-level criminals out of overcrowded jails. Top Republicans and police aren’t happy.

Published 4:00 pm Tuesday, May 21, 2019

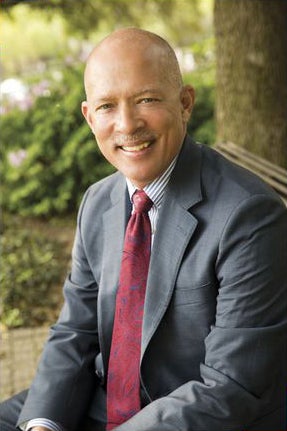

- "I’ve been in criminal justice for 37 years, and I’ve seen people steal because they’re hungry," says Dallas County District Attorney John Creuzot. (from social media)

The Texas Tribune

texastribune.org

Dallas County District Attorney John Creuzot announced policy reforms last month that he said would be “a step forward” in ending mass incarceration in Dallas. His plans include decreasing the use of excessively high bail amounts and no longer prosecuting most first-time marijuana offenses.

But part of his plan included a decision not to prosecute thefts of personal items under $750 that are stolen out of necessity. Immediately, Creuzot came under fire from state officials and police leaders who said the policy was irresponsible and would encourage criminal activity.

Creuzot said he didn’t arbitrarily pick that $750 threshold — that’s the value of stolen items that state law dictates will result in people being charged with no more than a Class B misdemeanor.

“I’ve been in criminal justice for 37 years, and I’ve seen people steal because they’re hungry, and I’ve seen the system react where the cases are dismissed or react in a more harsh manner where incarceration is requested,” Creuzot said. “But the reality of it is putting a person in jail is not going to make their situation any better.”

But the Combined Law Enforcement Associations of Texas, the largest police union in the state, called for Creuzot to step down. Gov. Greg Abbott fired off a series of tweets criticizing the policy and wrote a joint letter with Attorney General Ken Paxton that said the DA should reconsider his position and leave criminal justice reforms up to the Legislature.

“Reform is one thing. Actions that abandon the rule of law and that could promote lawlessness are altogether different,” the letter said.

Creuzot’s policy and the ensuing backlash highlight growing tensions among local district attorneys who want to reform a criminal justice system they say is broken and other public officials who believe that letting criminals skate could make cities more dangerous.

And Dallas is far from the only place in Texas — or the United States — where such debates are playing out.

“There is a movement across this country to ensure that our criminal justice systems are really about justice,” said Brianna Brown, deputy director of the Texas Organizing Project, which endorsed Creuzot in his election last year. “I think there’s been a real wake-up call, especially on the progressive side, about how do we figure out a way to really make an impact in everyday people’s lives, in particular folks of color who have been so disproportionately impacted by the kind of policies that have come to warehouse black and brown families across this country.”

A new area of reform

District attorneys, the elected officials responsible for prosecuting crimes on behalf of the state in the jurisdictions where they reside, have immense discretion in the cases they choose to pursue — or ones they choose not to prosecute.

But it’s only been in recent years that DAs across the country have begun tapping into this power, enacting policies they say can go a long way to ending problems like mass incarceration and court docket overcrowding in their jurisdictions.

“The system is bursting at the seams. There’s not a lot more room to put people, and we have to find a way to shrink the system,” said Jay Jenkins, Harris County project attorney with the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition. “The efforts at reforming police thus far have proven not effective at treating the system. The efforts of judicial accountability have not proven effective at shrinking the system. And so the reform movement is moving to the next most important person in this process, which is the district attorney.”

In 2016, District Attorney Kim Foxx in Illinois outlined policy reforms that included declining to charge shoplifters with a felony unless they stole more than $1,000 worth of goods or had 10 prior felony convictions — a huge leap from the $300 threshold for felony theft convictions in previous years.

Two years later, Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner said he would handle retail theft cases under $500 as summary offenses, which are similar to traffic violations and often result in fines.

This year alone, district attorneys in Massachusetts and Missouri included theft policies among their lists of reforms. In Suffolk County, Massachusetts, District Attorney Rachael Rollins said she would decline to prosecute shoplifting and larceny, or theft of another person’s property, under $250. And Wesley Bell in St. Louis said he would issue a court summons, not an arrest warrant, for certain low-level felonies — including theft of items over $750.

The list goes on; in the last two years, district attorneys in Maryland, Florida, North Carolina, Washington and Tennessee have enacted various reform policies in their jurisdictions.

But it’s just not just theft cases that prosecutors are beginning to treat differently — and such policies have reached Texas, too. This year, Bexar County District Attorney Joe Gonzales announced he will soon begin a cite-and-release program that would give police the option of issuing a ticket for misdemeanor offenses like possession of marijuana, theft and driving with an invalid license. Travis County District Attorney Margaret Moore announced last month that she was expanding Travis County’s practice of declining charges for cases involving trace amounts of drugs. And Harris County District Attorney Kim Ogg announced in 2017 that she would send people convicted of certain marijuana offenses through a diversion court.

But advocates say the success of such reforms can be hard to measure. For one, many of these policies are brand new or only a few years old, and there is good data to indicate their outcomes. And success depends on what metric jurisdictions are measuring, like jail populations or the number of cases on local court dockets, for example.

“It’s still such a new area of reform that we’re not sure exactly how it’s going to end up,” Jenkins said. “But it’s encouraging that the reform movement has expanded beyond just police accountability and beyond judicial accountability.”

He said it’s also a reflection of local jurisdictions’ need to prioritize criminal justice resources. When Creuzot took office, for example, the city had a backlog of 10,000 cases.

“It’s about discretion to tell the police that that is not worth our time and resources,” Jenkins said. “The DA’s office has a pie, and they can only spend that pie of resources. And they can choose, like most DAs, to spend that pie prosecuting low-level theft offenses and continue this cycle where we put poor people and black and brown people in jail, or they can take those resources in that pie … and commit those to solving rapes and murders.”

Law enforcement fears

But police officers in Dallas are still wary. While Michael Mata, president of Dallas Police Association, said some of the reforms Creuzot implemented are needed, he said police officers in the city feel they’re being blamed for enforcing the law on theft. He said officers already do everything they can to help people who steal because they are poor or hungry, and that “going public” with the policy is harmful to officers.

It’s creating a “belief that it’s an option, that we are choosing to enforce laws,” Mata said. “We are mandated to, especially if we have a complainant and he’s telling us, ‘No, I want to be a complainant, I want to file a complaint,’ and we have to. And that’s misinformation that erodes an already eroding relationship with the public. This isn’t helping us.”

Despite the opposition, Creuzot says he plans to stick to the reforms. As a felony district court judge in 1998, he founded the Dallas Initiative for Diversion and Expedited Rehabilitation and Treatment, known as DIVERT court. The court diverts nonviolent drug offenders to treatment and counseling programs instead of traditional criminal justice processing.

The program resulted in a 60% reduction in recidivism and saved over $9 for every dollar spent on the court, Creuzot said. He said his new reforms are largely based on the success he’s seen in the DIVERT court.

A week after the announcement of his latest reform plans, Creuzot said in a statement that he was not directing police officers to stop making arrests for theft offenses and that the personal items in the plans included necessities like food, diapers and baby formula. And he said thefts for economic gain will still be prosecuted.

“Even $750 worth of bacon will get you prosecuted under my rules because you’re a thief. You’re not stealing $750 worth of bacon to eat it; you’re going to sell it,” Creuzot said.

Creuzot said the reform will affect only a handful of cases. The number of people who steal out of hunger, for example, is very small, and they’re usually stealing less than $100 worth of food — which is a Class C misdemeanor and is handled in municipal court.

He’s also pointed out that much of what he is implementing was part of his successful campaign for district attorney in November.

“People will say what they want and how they want, and I have no control over that. I know what the research shows; I know who’s supporting me — some of the most conservative individuals in the state are,” he said. “I won by 60%, so obviously these reforms and these ideas have support in the community.”

The Texas Tribune is a nonpartisan, nonprofit media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them – about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

See also: PA chief provides crime insights